Yes, it sounds a bit absurd. But in order to scale up production, I’ve started experimenting with using propane burners for charcoal production. This is, ideally, an interim step as I go to larger production equipment, but it’s a nice step up in size from the equipment I was using. Larger pots, larger burners, and about 3 pounds produced per batch.

Of course, I ended up with another wood fired solution… But I did start with propane!

Experiment 1: Basic Function Test

I haven’t had time to get the larger pots modified yet, so I decided to try out my fancy new burner with the small, bottom venting pot - and I learned several important things! First and foremost, I need a bigger propane tank, because this burner can consume way more propane than a 5 gallon tank can provide in the winter. Or perhaps there’s a flow limiting device somewhere in the chain.

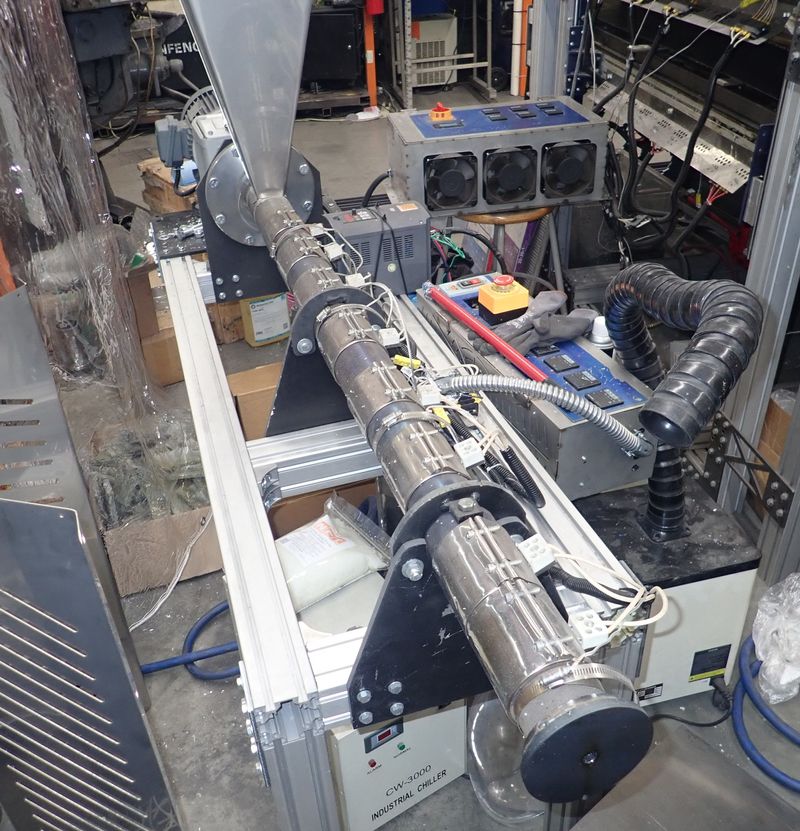

My burner here is a 200k BTU propane burner - a massive unit that’s capable of burning north of 2 gallons an hour of propane. My pot is rather smaller than this burner is designed for, so I had to be a bit creative.

Initially, I started out with the pot supported on a couple pieces of rebar - it’s up where it’s designed to be, and while I wasn’t sure how it would work that far from the burner, isn’t that the point of experimentation?

I lit the burner, cranked it up, waited, and eventually got what I was looking for - wisps of smoke escaping from the top of the pot, and a bit of reburn down below as it vented under the pot! The problem here was that it never really ramped up - it should, once it starts burning, rapidly get into the “jets of fire” territory, and this just wasn’t. There just wasn’t enough heat getting into the pot to really light stuff off, so after a reasonable period of time, I shut it down and contemplated my options.

One of which involved just setting the pot directly on the burner! The stainless steel elbows provide some of the lift needed so the flame can burn under it, and… hey, maybe this will work. Initial results were promising, with some pretty good orange flame (which isn’t propane) coming out in a hurry.

After a bit longer, it became clear that this was working far better - I had a solid amount of offgassing burning under the pot, and I was able to pull the propane flow back to barely running for a while as the pot heated on the offgassing. This is exactly what I was hoping for - though there’s still a lot of heat ending up “not in the pot” because of the wide open spaces around it.

I’ve found that if the pot is really hot (glowing), it gets orange flames around the edges just from the propane - if you turn back the jets almost all the way, you can see if the orange flame is from offgassing wood (the process is still going), or from the propane reacting with the high temperature metal, somehow (which is just the gas jets). But usually by the time the pot is glowing, the process is done.

After it stopped flaring, I left the propane burner running for another 5 minutes or so, and then shut things down. The result? Yup, it’s charcoal! It’s not great charcoal - but it certainly qualifies.

But this really isn’t the intended use of this burner arrangement. The pot is far too small, and I can run this in the Solo Stove. It’s time to go bigger!

Experiment 2: Large Pot with Jets

When I got the burner, I ordered a few larger pots to go with it. They’ve got welded handles (less to fall off from melting rivets), and hold quite a bit more wood. I have a few ideas as far as modifying them for gas jets goes, and there was one particular design I was able to more or less sort out with what I have around the hill: The bottom jets.

After some abusing of the pot with a drill press and some old taps, I managed to get my four jets screwed in fairly tightly to the bottom. It’s not perfect, there’s some leakage, but I’m happy enough with how they work. You’ll notice that I’ve offset them from each other - my goal, which it turns out was successful, is to get some swirl going under here to help things mix and to help ensure there’s stable combustion of the venting gasses under the pot.

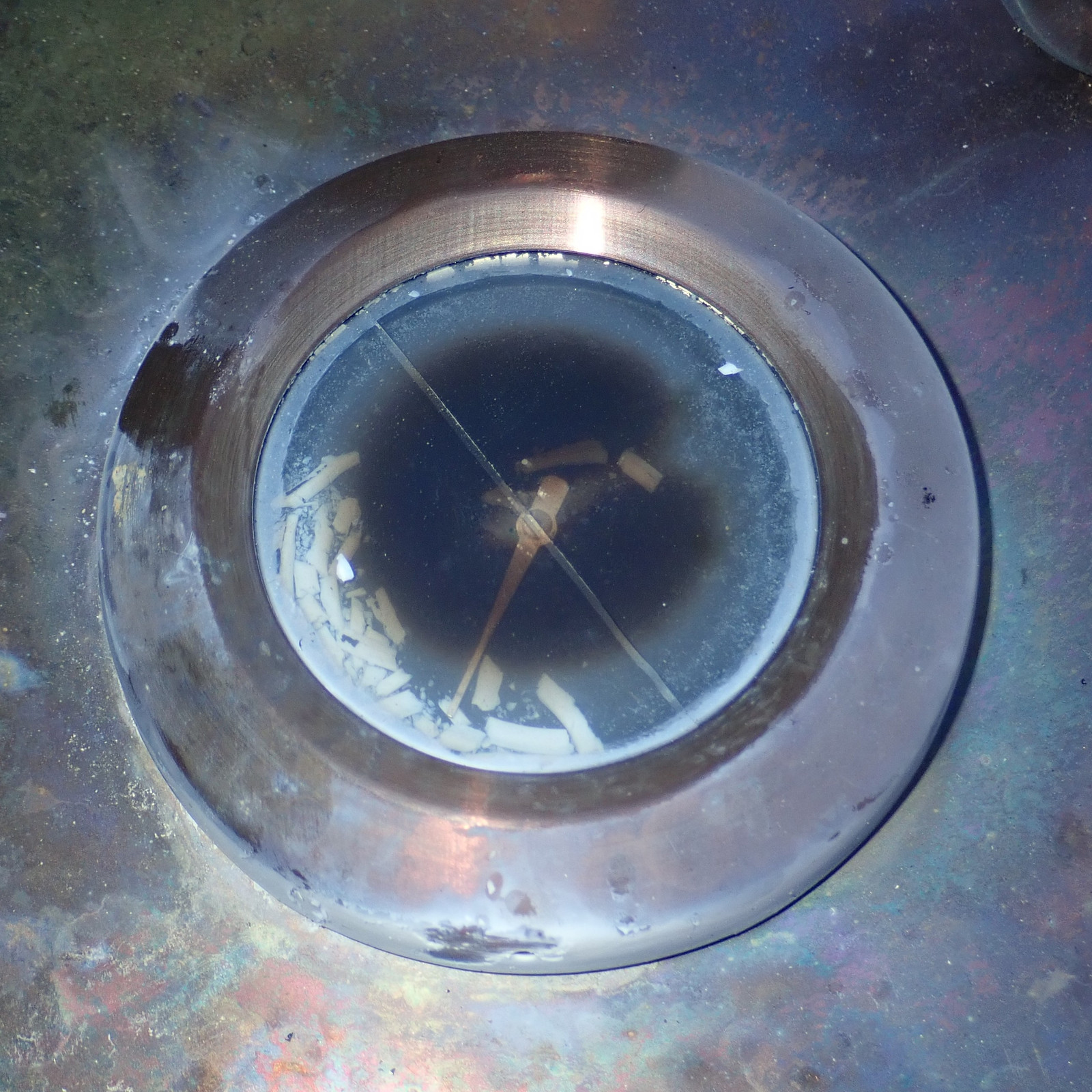

My smaller pot has demonstrated that with small feedstock (dried mulch, mostly), the jets will clog from charcoal falling in. I’d expected that was a possibility, so I also installed some of my pipe Ts. The theory is that these will keep the charcoal debris from clogging the jets, and allow me to use more small mulch as feedstock if I so desire.

For my first run, I went with just an assorted sampling of wood. Some larger stuff, some mulch, etc. This leads to a good feel for the process, but is less than ideal for production - it’s easier to have everything about the same size, as it’ll cook off together. Here, some pieces are done while others are still heating up - but it’s good to be able to see how well the process runs at a range of sizes.

The gap between the burner and my pot is larger than I’d prefer, and I plan to fix that, but it didn’t take long to get some venting gases lit off. Unfortunately, you can see that the ring around the base is tight up against the pot - so there’s this dome of carbon dioxide under the pot, and stuff just wasn’t burning well. It would sort of bubble under it, and generally not burn along the pot where I was hoping. This became quite obvious, so I decided to cool things off a bit and fix it.

The fix, at least for now, is simply a few chunks of rebar. They’ll get hot, but they don’t care. This gives enough of a gap between the support ring and the pot for gases to flow out - which means the flame and heat can impinge more directly on the pot. Remember, glowing is good!

Heat loss is my enemy here. It’s far too hard to keep the pot hot enough, long enough, so I’ve added some rock wool insulation from back when I built my office. Right now, it’s just on the top (with a weight to keep the lid pressed down except for overpressure venting), but I plan to insulate a lot more of the pot over time with this stuff and work out the details of how to keep everything really warm for long periods.

The ports through the side serve rather effectively to let me see the process of the venting - though the camera rather exaggerates the amount of red coming off the ring. It was red, just not this red. But the flames vent around the base of the pot and heat everything up exactly as desired!

Crank it up and let it run! I learned a few things during this run that were new to me. First, the air vents for the propane burner are open too wide, stock. Unfortunately, the screws are also very tight - so I need to try an impact on them, otherwise “stuffing some insulation in the intake” does a decent job of restricting air. If the flames are leaping off the burner as the flow increases and really “roaring,” the mixture is too lean. They flames should be mostly blue with a touch of yellow on the tip, and after I made that adjustment, the burner behaved a lot better. It also seems that the draft through the burners has a real impact on how the vents burn - they burn far better when there’s more air, amazingly enough… if I turn the main burner back, the vents will stay lit, but the fire changes character somewhat. I may play with some air augmentation from below that isn’t through the burner. But it certainly burns well, and this design is able to reburn almost all the venting gases. I had very little escaping the top.

The result, though, wasn’t great. It was too hard - I’m learning what well cooked charcoal feels like, and I knew this stuff wasn’t fully cooked. However, it had burned down enough that I was able to compact all the product into my smaller pot and burn it in the firepit after another firepit evening (that went rather long, so I had a lot of coals). This clearly burned off more from the mostly processed charcoal, and I ended up with something closer to what I expect out of it. It meets the requirements for biochar - I did have it lab tested - but I’m not terribly happy with the results, and I went through quite a bit of propane to make it, which somewhat defeats my goals of making it with renewable resources.

The main takeaway here is that heat isn’t enough - you also need a good bit of time at heat for proper biochar. The fuel grade charcoal can burn for less time, as some of the residual oils and such are actually useful for fuel purposes. But I’m not (mostly) making fuel. I want to make good biochar, and that requires a longer cooking time.

But I’ve got a few ideas…

Adding Science

So far in this process, I’ve been more or less “flying blind” - I can tell based on how the output feels if I made good charcoal or not, but I don’t have a sense of temperatures in the pot beyond “Really hot” - the base of the pot, in the firepit, is typically glowing a dull red.

So I found a few high temperature BBQ thermometers, reading up to about 550C or 1000F, and I’ve installed them in pot lids to see how hot things get inside!

They poke through with a little metal bit - and if you’re curious about what looks like a tarry layer on the inside of a lid, that’s exactly what it is. My big pot isn’t getting hot enough (I know this based on the output), and it’s condensing layers of wood tar that it hasn’t gotten hot enough to burn off. It’s a rather sticky mess, and while I’m sure there are uses for it, dealing with “massively sticky stuff” just isn’t my idea of a good time. I’d rather figure out how to get the whole pot hot enough to burn it off for energy instead.

The Tumbleweed Special

Another little bit of experimentation I’ve done is what I’m calling the Tumbleweed Special. If you stuff a pot full of tumbleweed, it charcoals down just fine, and you end up with a nice fine bit of very cooked charcoal - out of something that’s otherwise a genuine nuisance around the hill! If the wind gives you tumbleweeds, make charcoal!

The density isn’t great - I don’t get much result out of the pot full. But it’s properly satisfying to turn wind-blown tumbleweed into biochar!

Experiment 3: Back to the Solo Stove

I concluded that I had two problems with the propane fired system: the loose shroud let too much heat escape, and it didn’t really let the burning gases tuck tight against the pot to transfer heat in. I’d not thought about running this pot in the Solo Stove before because it would have choked out the fire - but… how would it contain the venting gases? Would they burn well?

My first Solo Stove grate burned out - I was able to get a warranty replacement for normal firepit work, but I’ve also got the pellet insert. Some experimenting with fit indicated that I’d still have a small gap between the larger pot and the edge of the ring. Will it work? Time to experiment! I put about two inches of pellets into the bottom of the stove, ignored every warning that says “Don’t light this with kerosene” and lit it with kerosene, and waited for things to catch. Interestingly, if you’re trying to light pellets, putting a couple tumbleweed in while it’s starting off really helps get things going - the combination of draft and reflected heat seems to do a marvelous job.

The pot went in, and pretty soon things started happening that were quite encouraging. Flames licked up the sides, and before long it was clear that the temperature was rising quickly, and that I was burning vented gases off - both at the base from airflow through the grate, and up high, from the secondary burn airflow - which directed the tongues of flame right into the pot.

After half an hour or so of this, the pot was very much burning off in the desired manner - lots of flames licking around the top, some venting from the lid (I’ll put weight on the lid, but I refuse to screw it down as this is a safety vent - see Experiment 4 for details here), and some very nice temperatures.

North of 700F - not too bad! Though also not too great. I never saw things climb much higher, and my thermometer remained quite intact afterwards. I’ve discovered that despite being a “1000F” thermometer, these start boiling their paint off around 800F - which, yes, is a bit of a weird issue to have.

The charcoal coming out was decent enough - certainly useful for biochar, but it also was heavy, and still clearly had a lot of stuff not burned off. I’m doing more research as to the ideal temperature for biochar, but there is absolutely a difference between low and high temperature production, and this was low temperature production.

Experiment 4: But What If I Shroud It?

A major problem I’m learning about is that if the pot sticks about above whatever is shrouding it, the top part remains far cooler than the lower, shrouded part. Being able to radiate heat off to infinity versus having it reflected back makes a big difference in temperature, and so I’ve frequently been finding the exposed part of the pot covered in carbon soot, while the lower parts have it all burned off. Useful, if you want to collect the lampblack, but not ideal from a “maximize the energy redirected into making charcoal” perspective.

I was debating having a friend make me a shroud of something when I contemplated the merits of my stainless steel propane burner shroud. A few quick measurements later, I removed it from the burner and proceeded to stick it on top of the Solo Stove - where it fit perfectly!

Another couple inches of pellets, another load of charcoal, some kerosene, some time, and I had another fire going nicely. Stack the pot in, and put the shroud on, then wait to see if it makes a difference.

It didn’t take long to watch the temperature climbing rather more rapidly than the previous test, and to conclude that this was working far better at redirecting heat to where I want it!

Reburning venting gases from charcoal production is a textbook example of a positive feedback loop - the hotter you get, the more gases are generated. The simple addition of a shroud above the pot amplified this loop quite a bit, and before long it was clear that the pot was running FAR hotter than before, with a lot more generated gases generating a lot more heat. Midway through the process, I heard something “thwupping” fairly rapidly, and it turned out to be the lid of the pot, lifting and venting off gases as the pressure exceeded the weight of the lid and the weight on it. This is why I don’t want to clamp the lid on - it serves as a useful pressure relief. However, I might add another vent or two on the bottom of the pot, or increase the diameter of the jets I have down there, because it’s clear that I can generate more gas than they can vent at a reasonable pressure.

Of course, if you’ve got a fire going, you may as well roast a marshmallow or two on it. This just doesn’t make a good marshmallow roasting fire, though. It’s far, far too hot, and it’s almost impossible to find a spot that won’t light it on fire, while still getting enough heat in to roast it. My son certainly enjoys the frequent fire experiments!

The results, though, are clear. This ran far hotter than the previous test. In addition to the charcoal coming off being more glass-like (indicating more of the volatiles were burned off), the thermometer… didn’t really survive. At some point during the testing, it got quite a bit hotter than the last one I fried. I really should invest in some thermocouples, but at this point, I don’t need a thermometer anymore - I know it’s getting nice and toasty.

The shroud is deeply discolored from the heat as well. It gets warm in there, as hoped for!

And I still have my burner. I’ve got a few ideas to mess with to improve this - but, for now, I think the right answer is “wood pellets and the spare Solo Stove.” I can make 3 pounds of good charcoal per batch, and I’ll probably stick with this until I get a better feel for market demand - which, hopefully, means I’ll have an excuse to Go Bigger!

Comments

Comments are handled on my Discourse forum - you'll need to create an account there to post comments.If you've found this post useful, insightful, or informative, why not support me on Ko-fi? And if you'd like to be notified of new posts (I post every two weeks), you can follow my blog via email! Of course, if you like RSS, I support that too.