It’s been a little bit since I’ve torn apart a new battery pack! The last new-to-me pack I pulled apart was a 26v BionX battery (which, I’d add, I rebuilt to nearly twice the stock capacity by filling all the space with cells). And I’ve got this cute little DeWalt 20V MAX battery pack (model DCB200, 3.0Ah) that’s just not behaving right. It would charge, but then only show one LED on the status bar. I got it for $6 at a pawn shop when I asked for defective batteries.

Well, I’ve got a dead battery on my bench - that means that it’s time to tear it apart!

And you know you want to see what’s inside!

Read on for an awful lot of photos inside this solidly built battery pack.

Specs & Warnings

On the back, I’ve got specs about my DCB200 Battery Pack (Made in Korea). It’s a 20V (Max) pack, 3.0Ah, and claims to be a 60Wh pack. Type 2, whatever that means.

I’m going to grumble a bit here. They call the pack a 20V pack, claim it as 3.0Ah, and then say “60Wh.” This is the math, but it’s not a 20V pack by anyone else’s standards. This, in normal terms, is a 18.5V pack (5S pack, 3.7V/cell). To call it a 20V pack requires a nominal voltage of 4V/cell, which is just weird (and not what they have). Anyway, just my thoughts. I’m clearly not a tool pack marketing guy.

Amusingly, the warnings here don’t say anything about not disassembling the pack, so I’m good!

Except, I apparently did charge it while damaged. Spoiler alert!

Pack Interface & Voltages

The pack has two significant interfaces: The power interface, and the “How charged is it?” interface.

The “How charged is it?” interface is simple enough. Press button, receive ~bacon~ LED status lights. Zero, dead. Three, fully charged.

The electrical interface is a bit more interesting - and, really, quite a bit of fun!

The leftmost slot is a double connector for the positive terminal. This is a full height terminal (two contacts). The rightmost slot is the same thing for the negative terminal. These always appear to have the full pack voltage on them.

In the middle are some other terminals of interest. From left to right, top to bottom: TH, ID, C1, C2, C3, C4.

A tiny bit of experimentation with packs demonstrates that C1-C4 are actually the individual cell bank voltages, conveniently brought out for my use!

If you look at the charger side, the pin that makes contact with the “ID” pin is longer by a tiny bit than the others (the top right of the center 6 pins). This pin seems to be always at low potential, and there’s a bit of a voltage floating on the charger pins when there’s no battery. I suspect pulling the ID pin low brings the charger circuitry online, but I don’t care to actually mess about with my charger since I use it.

I grabbed some voltages from a good pack of mine (I’ve got 2 good 20V Max batteries). Everything is measured relative to B-, with the relative voltages from the previous reading in parentheses. My pack is fully charged (20.43V, 3 LEDs, solid charger light).

C1: 4.08V (4.08V)

C2: 8.17V (4.09V)

C3: 12.26V (4.09V)

C4: 16.34V (4.08V)

B+: 20.43V (4.09V)

This is a healthy pack. The per-cell voltages are almost identical (within 0.01v), which means a well balanced pack in good condition. Conveniently, this also means that the cell group voltages are externally accessible. This is great news for testing a pack!

Also of note is that the cells are charged to 4.1V instead of the more typical 4.2V. This is great news for longevity - sitting at 100% state of charge (which, for these cells, is 4.2V) is bad for calendar life. Charging almost all the way (but not quite to 100%) means they’ll last longer on the shelf when charged - and most people store tool batteries charged.

From this “dead” pack right off the charger? Let’s see!

C1: 4.08V (4.08V)

C2: 4.10V (0.02V) (uh oh)

C3: 8.19V (4.09V)

C4: 12.19V (4.00V)

B+: 16.37V (4.18V)

I did double check this, thinking I’d made a mistake in transcribing numbers. The C1-C2 reading is 22.9mV. This isn’t good. That’s a stone dead cell bank, if it’s accurate. And the rest isn’t very pretty either. You’d expect to see a nicely balanced pack like mine, not a voltage horror show like this. If the voltages are accurate, there’s something seriously wrong with this pack.

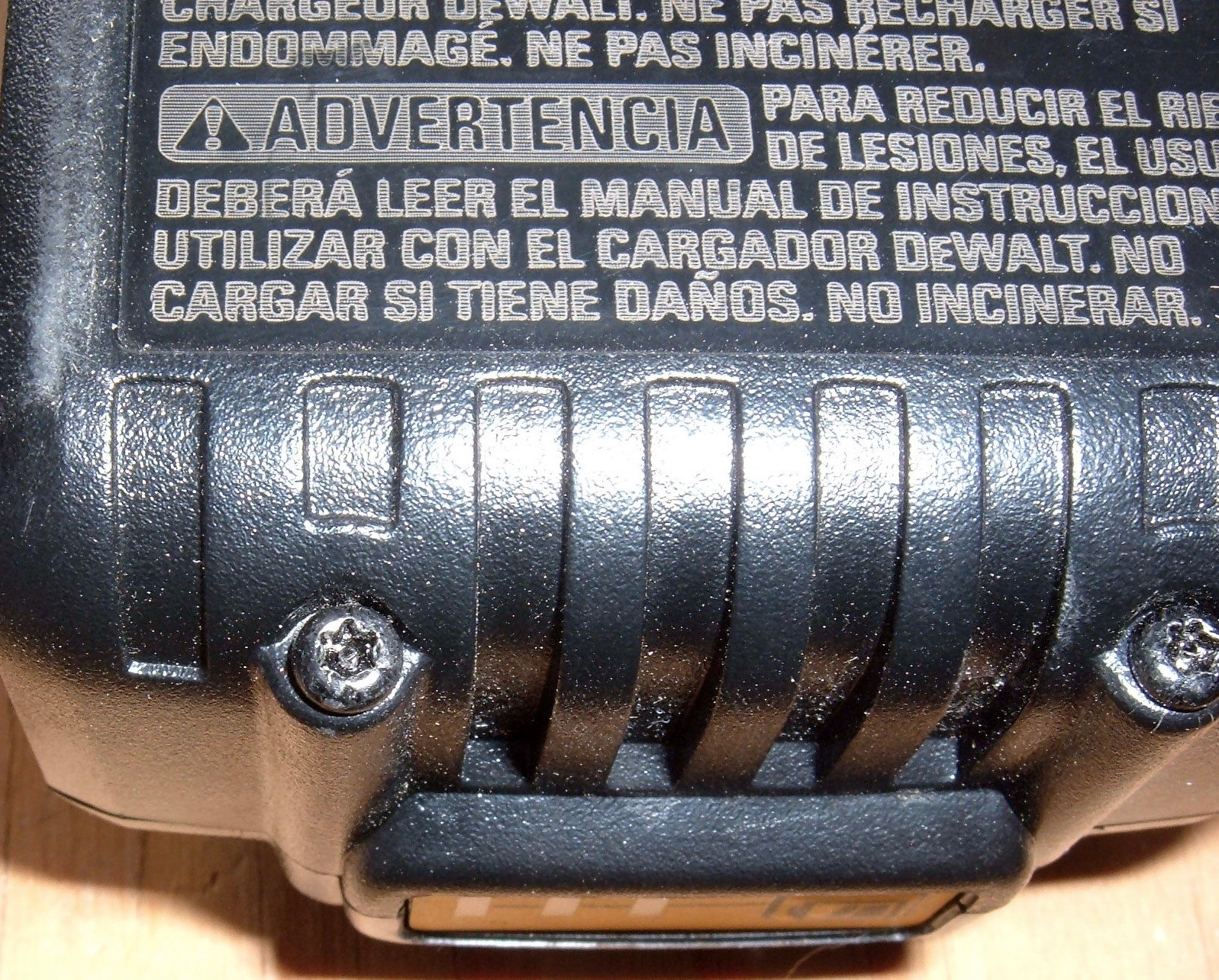

Disassembling the Pack

Pulling the pack apart involves removing 4 Torx screws with center pins. These, obviously, don’t work with regular Torx head bits. I hear a rumor that things like center pins mean they’re a “Security Bit” intended to keep people out.

Fortunately, my shop has something called a “100 Piece Security Bit Set.” Any good electronics shop does. So, bring your “security bits trying to keep me out.” Hint: I brought it. It’s a T10 size Torx security screw, if you’re interested. One of which is very much included in this 100 piece set. It’s not even very creative…

Pack Insides

With the “Security Screws” out, the top comes off cleanly, exposing the pack guts and a really neat little spring for the pack release button. Sproing!

From this angle, the “double height” B+ and B- terminals are visible, as is the state-of-charge indicator.

Interestingly, it looks like the B+ and B- terminals are a different material than the cell-group contacts and the TH/ID contact.

The B+/B- terminals look like copper to me, with the rest being brass or something along those lines.

That makes sense, though. The B+/B- terminals are the ones carrying the power, while the rest shouldn’t ever be transmitting any significant amount of current.

Looking down from the top, there are wires running around to each side of the pack. These are almost certainly the voltage sense/balance wires. It’s interesting that they’re bare, but it’s fine inside a sealed pack. They’re custom bent to fit, and fit in perfectly.

The red and black wire on the left are going to the LED indicator. Based on the lack of any other wires, it’s likely just a basic voltmeter that lights up the LEDs.

One thing of note here: The battery is always connected to the terminals. There is no way that the BMS can cut off current if the pack voltage is low. It’s up to the tool to determine the cutoff point and refuse to work below that.

This also means that if you stick something in the terminals, you can get power out. Don’t leave it running and drain the pack, but this would be a really easy pack to repurpose should you care to do so. There’s literally nothing to do but jam metal blades into the B- and B+ terminals.

Removing the Battery Pack

There’s no real trick to removing the battery pack from the bottom part of the case. It just pulls out. However, it’s in there very tightly. Start with one end, pry (carefully - don’t short the pack out), and it comes out.

The wire between the battery pack and the output terminals is quite substantial, and is secured with an awful lot of solder. This is very clearly designed as a high power pack! Look at the size of the lug going into the positive terminal…

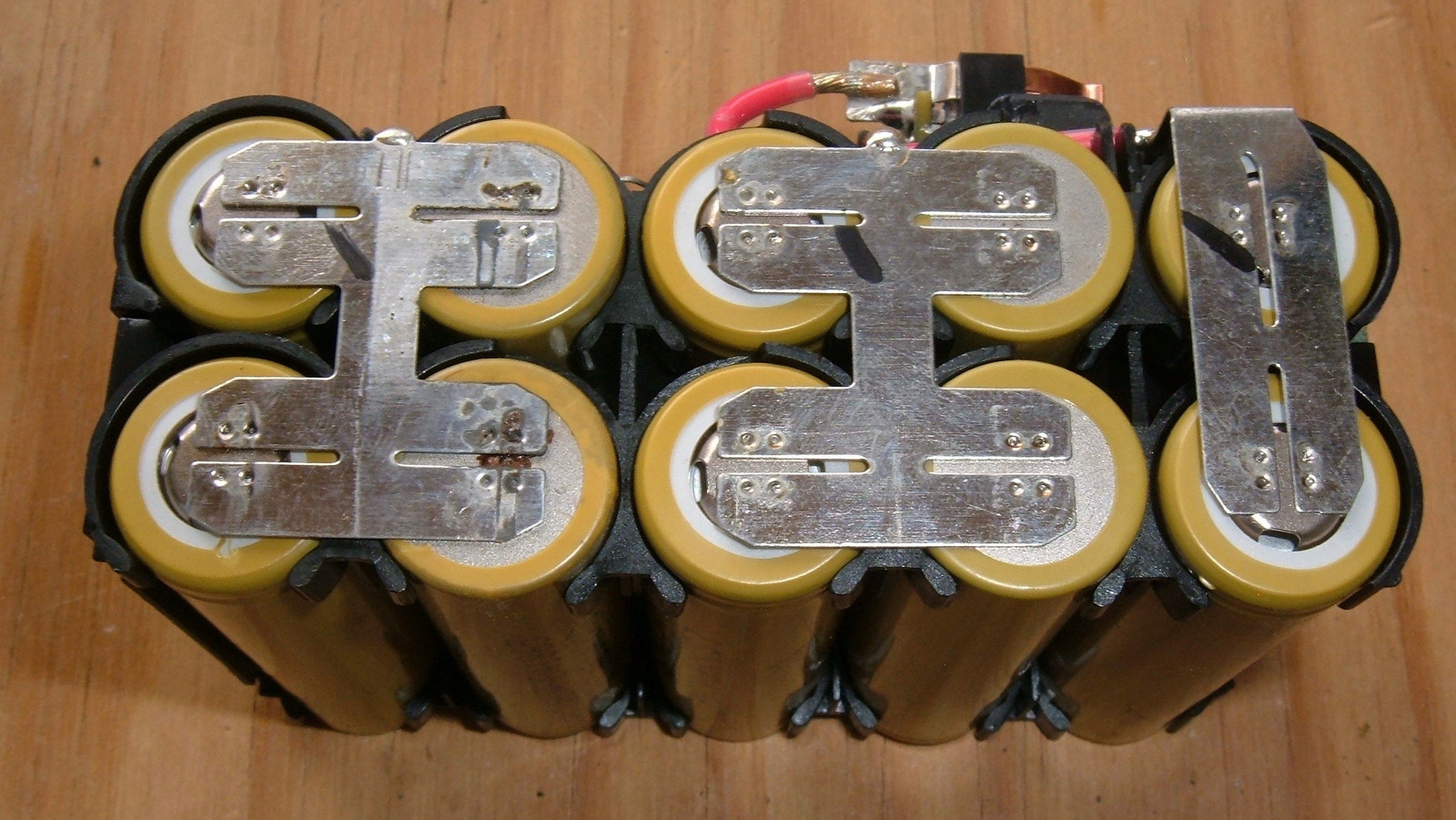

After a bit more prying, the pack is out. There are 10 cells (2P5S pack), and they’re held together with rather substantial interconnect strips. The pack claims to be 3.0Ah, which means each cell should be 1500mAh. Are they? We’ll soon find out!

The LED board is secured to the battery pack with some sort of goop. It’s not going anywhere.

Cells and Interconnects

One of the cells is very conveniently oriented so I can read the model number.

The model number is LGDAHB41865. This works out to be a LG HB4 cell - which is a 1500mA cell rated for a 30A discharge! The battery chemistry is NMC (Lithium Nickel Manganese Cobalt Oxide or LiNiMnCoO2). This is one of the newer chemistries, which is nice to see. They’re in every way better than the early lithium ion chemistries.

This is a solid, solid choice for a power tool pack - and not a cheap choice either! DeWalt didn’t cheap out here with last year’s discount cells. People have tested this cell (it’s popular for vaping as well), and it’s a legitimate 30A cell.

With batteries, one can generally get a lot of energy (watt-hours) or power (watts), but not both. These are hardcore power cells - a single cell at 30A is putting out over 100W! The low capacity (1500mAh - below half of what a high energy cell can do) is the price you pay for a cell with that kind of power output.

The observant reader may note that the cell in the middle here, with the model clearly visible, looks a bit off. And, you’d be right. This cell is the 20mV group - even after charging.

The plastic wrapper on that cell is incredibly brittle compared to the other cells. It seems like it shorted out and overheated, or overheated and shorted out. I have no idea why, but it’s quite dead. Not knowing the pack history, I don’t know if it was a cell defect, or if something happened to it. But these two cells aren’t even nailed to their perch. They are dead as granite. What likely happened is that one of the cells shorted internally, and the other one dumped its current through as well. Exciting - and not in the good way.

The interconnects here are thick, massive, and well spot welded. I’m not sure if this is a machine built pack or if it was built by humans, but I’m leaning towards “humans” - the placement of the “H” interconnects isn’t identical between the left cluster and the center cluster, and the rightmost strip is somewhat off center. I don’t see why one would configure a machine to do that.

The shorted cell shows some corrosion and discoloration on the ends (the second pair down, left side and right side). Perhaps it overheated enough to damage the coating on the case? I’m not sure. This is the negative end, and it doesn’t look like it’s burned through (I scraped the corrosion off and it looked normal), so… still no idea what happened. Nothing good, that’s for sure. The top left cell also looks a bit off (the discoloration on the positive terminal doesn’t exist on any other cells).

Skipping ahead slightly, I measured the thickness of the interconnect strip used. It’s a hair under 0.012” - so 0.30mm, or twice as thick as the common 0.15mm nickel strip used in ebike battery packs. Again, a beefy, beefy pack. For what it’s worth, I can’t spot weld this stuff - too thick. It takes some serious amps to spot weld 0.30mm strip.

Getting to the BMS

Next, I want to get the BMS off - that lets me get deeper into the pack, and figure out what’s going on with the BMS board (not that it’s much of a management board).

The solder connections are substantial. This pack really is designed to carry a lot of power. Lots of solder, lots of thermal wicking from the nickel strip… I’m going to need a bigger iron than I normally use!

Fortunately, I have such a beast, warming up nicely in this picture. This is a Portasol 125W butane iron, available for around $70 on eBay. There are times for a precision temperature controlled iron, and times for a hot running beast of an iron. With the butane flow turned up, this thing is the second. Hot, massive, and will desolder almost anything I come across.

Also, a solder sucker for some of these solder globs. Because why not?

This unit took more heat than is usual to desolder stuff. Lots of solder, lots of thermal wicking, and lead free solder leads to needing a serious amount of heat. Light the iron up, let it get good and hot, get some solder on the tip, and go. There’s no way I could have popped the main power wires free with my normal bench iron.

A bit of fiddling, and the BMS is clear! The wire routing for the balance wires is really well done. I’m very impressed with this pack so far.

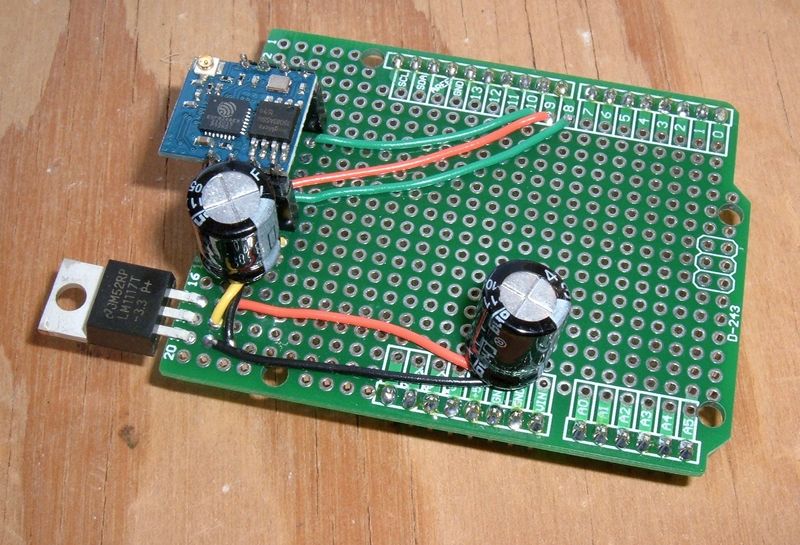

The BMS, free and clear!

BMS Board

I refer to this board as a BMS, but I think it’s probably better to call it a balancing board, or a balancer board. And I’m not entirely sure I understand its point.

The back of the board is entirely passive components. Some resistors, a few capacitors, and a diode. Plus some hefty solder joints to hold the prongs in place.

Looking down into the gap between the prongs and the board, there’s what appears to be a small IC in there, and a few more passive components.

The bottom of the board shows another small IC down to the left, and what looks an awful lot like a thermistor in the top right. After removing the conformal coating, I measured 10.68kΩ at 21.6C - so probably a standard 10k/25C thermistor. For those unfamiliar, a thermistor is just a resistor that changes resistance with temperature. It’s an easy way to monitor pack temperature. Unfortunately, this one is really only monitoring pack temperature - not cell temperature.

It’s hard to see in the photos, but this board has a nice conformal coating on everything. A conformal coating helps keep water off the board, and generally improves reliability in rough environments - which tool packs will certainly see. There’s basically no excuse to not have one in 2016.

I played with it a bit, and it certainly seems to be a balancer, but I don’t understand why it exists. Whatever functionality it allows for can be done externally on the charger. The charger has pins for all of the parallel groups, and an external balancing charger is more reusable than a single pack balancer. On top of it, this BMS can’t even protect the pack from an overdischarge or any sort of fault condition. It might be able to alert the tool to an imbalance condition, but the charger could also refuse to charge the pack in that state. So I’m a bit lost as to what, exactly, this board does. Given what it can’t do, I’m having a hard time figuring out why DeWalt even put it in.

LED Status Board

The LED status board has a sheet of plastic over the top - great for helping keep the environment out.

Beyond that, the switch, when pressed, applies pack voltage to a system that lights the proper LED based on the voltage. That’s all it is - a basic voltmeter.

So, of course, I set about testing it to find out what the voltages involved are.

Results from the testing:

1 LED: >15.3V (3.06V/cell)

2 LED: >18V (3.6V/cell)

3 LED: >19V (3.8V/cell)

Sane enough, though one LED means you really should be charging it now. There’s no reason to run a power cell below 3V, and 1 LED is almost there.

I did confirm that the BMS will balance cells. With voltage on the positive and negative leads, the balance leads have proportional voltage across them as one would expect for a battery balancing system. So, cool! Weird, because the charger could do it just as easily, but still neat.

Rebuild or Keep Going?

At this point, I have a decision to make. I can either stop pulling things apart at this point and rebuild the pack, or I can keep going.

I make the decision to rebuild or not based on two major factors: Rarity and cost.

Rarity

How rare is the pack I’m dealing with? For some of the packs I’ve rebuilt, they’re rare, and either very difficult or impossible to obtain a replacement for. If that’s the case, rebuilding it makes a ton of sense.

How hard is it to get a DeWalt 20V Max pack? Well… there are are over 800 listings on eBay - so not rare at all. You can buy them in nearly endless quantities at your local hardware store.

Cost

Cost is my other main consideration. If I can rebuild the pack radically cheaper than I can buy a new one, I’m likely to rebuild it. If I can’t - then there’s no real point in the labor to rebuild it.

For me to buy 10 of these cells, I’m spending basically as much as a new pack. BatteryBro has LG HB4s for $4.57/ea - in quantities of 50. eBay isn’t any better, at around $5/cell.

I can buy the 3.0Ah battery packs for $40-$50 shipped, all day long. You’re better off buying these packs to extract the HB4s than you are rebuilding them!

The Decision

This pack is not rare. And to obtain similar 30A rated batteries, I’ll spend more on cells in small quantities as I will on a brand new pack. Plus, I don’t have a spot welder that can deal with the thick interconnects. DeWalt sells these things in insane quantities, and it shows in the pricing.

So, there’s no reason to rebuild it. I keep going!

Oh, and if you are trying to rebuild one? Make sure you put a high amperage cell in it. Don’t go “Hey, I can double the capacity with some 3200mAh cells!” - they won’t like being subjected to the power demands of a tool pack. And those 9000mAh cells on eBay? Lies. Total, complete, bald faced lies. They’re recycled junk wrapped in a meaningless number.

Pulling the BMS Apart

This means pulling the BMS apart to see what’s on it - as much as I can.

The balance leads are easy enough. They pull off with a bit of fiddling.

They’re just standard header pin sizes, and they seat in a regular connector. Slick!

That nice green thermistor is right there too.

The leads going to the LED panel are nicely secured - they’re much more solidly connected than what I’m used to seeing in some of my teardowns. Excellent!

Removing the connectors is a lot harder than I expected. I tried to desolder them, and concluded that they’re just too large and radiate too much heat. I gave up after a minute or so of trying to free them with my big iron, and went to Plan B: Pliers and wire cutters. Which work, though that approach pulls the pads up with the main contacts. The heat bubbling in the lower right corner is me.

There’s nothing much on the front either. Only one IC (and I can’t read the model through the conformal coating, so I have no idea what it does).

Is Your Pack Bad?

If you’re here because you’ve got one that’s acting up and you want to see if it’s bad or not, I suggest doing what I did way up towards the top and measuring the voltages across the pins. You’ll need a thin wire to probe the contacts - though a pair of paperclips will work if you’re careful. Put the black lead of your voltmeter on the B- pin, and probe C1-C4 and B+ - you should see a steady increase in voltage as you go from terminal to terminal. If one of them is significantly less (like my 0.02V jump), you’ve got a dead cell bank.

It’s worth pointing out that this pack will happily spotweld any short circuit it sees. So don’t touch your paperclips to each other, or you will likely find them glowing within, oh, a second. Probably less.

Keeping Your Packs Alive

Lithium batteries are easy enough to keep alive, but there are a few things to know if you want them to last as long as possible.

Don’t charge them when they’re below freezing. You can use them in the winter - that’s fine. They’ll be a bit sluggish on output, but you won’t damage them. Charging them when cold, especially with the fast chargers that are common for tool batteries, will permanently reduce their capacity. Let them warm up before charging them. You also don’t want them to bake. Sitting in the trunk of a black car in Phoenix in the summer will also kill them early.

Don’t let them sit empty. That’s a great way to kill cells. Always charge them after use.

And, if you’re storing them for a long period of time, don’t let them sit completely full. It’s less of a problem with this pack (as it never charges to “full” by the cell chemistry), but charge them, run a tool for a few minutes, then store them if it’s going to be a few months.

Otherwise, just use them. Lithium cells don’t have a memory effect, so charge them when you get a chance, and have fun!

Final Thoughts

This is a solidly built pack that will do its job nicely.

The cells are solid 30A performers, which means this is a 60A pack (two cells in parallel add amperages). The 0.3mm nickel strip will handle plenty of amps, especially over the short distances involved here. The main wiring will handle lots of power as well. This is a very nicely built pack, and it’s entirely suited to being a power source for small tools.

Fully charged, at 20+V, that means it’s an honest 1200W power source (for, oh, three minutes until drained).

The only real complaints I have are that the BMS is really just a balancing board, and the thermistor is more or less useless. With the battery leads connected straight to the output terminals, there’s no way for the pack to cut off output - it’s up to the tool to not kill the battery pack. This is probably fine, since it’s unlikely that most people will use the pack for other purposes. But, if you do, don’t be stupid.

The thermistor hanging out on the BMS board also means that it’s more or less useless for tracking issues. All it will show you is a lagging reading of the temperature of the cells near it. It’ll provide a general idea, but nothing nearly so useful as a set of thermistors on the cells to find if one is running hot and suggest the user back off.

But from an end user perspective, this is an incredibly nice tool pack. It’s solidly built, is using great cells, and is capable of handling a ton of power. Use it as intended, don’t run it below 1 LED if you can help it, and it should keep you going for a long time!

Comments

Comments are handled on my Discourse forum - you'll need to create an account there to post comments.If you've found this post useful, insightful, or informative, why not support me on Ko-fi? And if you'd like to be notified of new posts (I post every two weeks), you can follow my blog via email! Of course, if you like RSS, I support that too.